On Shmuppin' 2: On Location

Planting the seed

It turns out there is more to say about shmups since my first post on the genre. I’ve kept playing them, I’ve kept thinking about them, reading others' experiences, getting a bit into the community, and even seeing some of it in person. They have become part of my life. I don’t think much of that is an exaggeration.

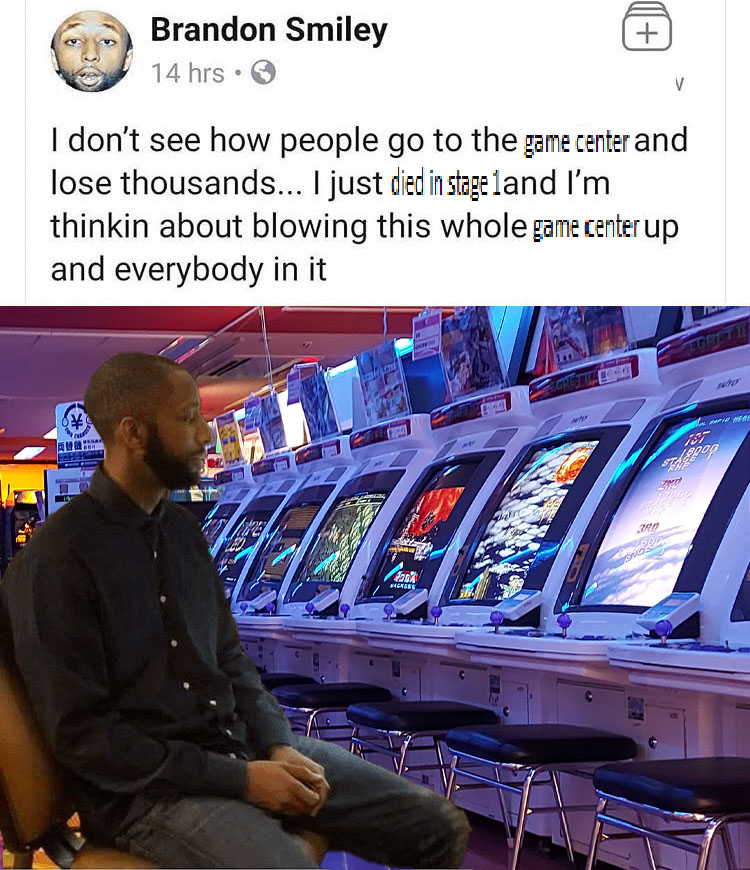

All my experience with this genre had been at home and so I wanted to experience them in their natural habitat — arcades. Where I live in Melbourne, Australia barely has any arcades left and those that somehow still linger only do so because they are branded and sold as wholesale “amusement centres,” with ten pin bowling, laser tag, VR arenas, escape rooms, ticket/prize games; they essentially amount to phone games in an extra large form factor for children’s parties. They do not foster the competitive or skill-based aspect of arcade gaming. There’s just no money in it anymore. The last remnants of hardcore arcade gaming in my city died off in the mid-to-late 00s with the closure of a couple of seedy fighting game focused establishments as they ended up being fronts for heroin dealers. And if not for some dramatic police raid, COVID killed the rest of them off — while researching for this post I found out two amusement centres I enjoyed visiting in my teens have since closed and one was bulldozed flat. I have recently learned about the existence of a large retro game arcade in Brisbane called 1UP, but even places like these are a dying breed; instead of being the norm they have to rely on nostalgia and the retro aspect to stay alive. Not to mention this might be the only one in Australia that doesn't seem to rely on being a "barcade" to draw in customers. This is why in April 2023 I visited Tokyo. My motivation for this trip arose partly from some life events transpiring the way they did, and part of it was that it just made sense to go. Once the seed was planted after playing Espgaluda 1 and 2 there was basically no hope for me; the flights almost booked themselves. Real arcades are not totally dead in Japan and so I had to see for myself what they were like.

If you want to play arcade games in Australia this is what you'll get.

The Pilgrimage

The first stop was the Taito HEY game centre in Akihabara, which I’m sure needs no introduction if you are a fan of the genre. It’s basically shmup mecca. All the classics are readily available to play, a row of CAVE titles standing proud as the first thing you see when entering the second floor of the building. I basically had to pick my jaw up off the floor when I first ascended those stairs. All these games in the flesh, empty cabs inviting me to dump my life savings down their coin chutes. Having only played these games at home and finally seeing them in person — I got it. I understood why people go crazy for these games. I understood why it is taking so long for them to die out. I understood why people pay top dollar for original PCBs and renovate their basements into retro gaming dens. I understood why shmup fans, while certainly fewer in number in comparison to other gaming scenes, are ravenously passionate. Besides the row of CAVE titles there were no shortage of other classics: heavy hitters from Raizing, Treasure, and Capcom just to name a few. There were also a few Exa and NESiCA cabinets, these in particular housing games completely unemulatable and prohibitively expensive for your average nerd at home. It was a good opportunity to try out some games I otherwise would have no chance to. And this was only the second floor. The third floor was filled with fighting games and puzzle games, generally being the rowdiest of the areas in HEY with the jeering and hollering of fighters going head to head. I specifically remember some guy in a checked shirt slamming buttons with such gusto, almost ducking and weaving in time with his character. It became clear that this place housed a different breed of gamer.

Another obvious stop on my Tokyo shmup tour was Mikado in Takadanobaba. This place was conveniently close to my hotel and provided the easiest access for my shooting game fix if needed. There was a really nice melonpan bakery just a bit up the road and the surrounding neighborhood is quite nice too. I enjoyed my nightwalks around in this area. Mikado was a much more local affair with fewer patrons, cabs, and less noise than HEY but certainly no less skill from the players — Mikado hosts competitions and tournaments with live commentary over a PA system which drew in crowds by the dozens. I had to squeeze through one such throng of people when what must’ve been the finals of a fighting game tournament were being held on a night I decided to visit. The shmups were mostly relegated to a corner on the second floor including some CAVE mainstays but also some others I didn’t recognize. I was able to put a lot of time into Espgaluda 2 here as the greatly reduced nearby foot traffic meant I wasn’t hogging the cab. In addition there were dozens of fighting game cabs, a few puzzle games, and a couple of Exa and NESiCA cabs too. Downstairs there were some light gun games, a few skill games, and a row of Shanghai mahjong solitaire machines that were my second pick if I had to wait for my turn upstairs. This place also had an amusingly small smoking room which basically amounted to a closet with an air duct attached at the top.

I visited several other arcades too. Taito Tachikawa had two shmup cabs (Espgaluda 2/SDOJ and Ketsui/ESP Ra.De.), and Gigo Shibuya had the jankiest SDOJ cab neglected in a dark corner of the top floor with malfunctioning speakers but offering two credits for the price of one. Several other arcades I visited had no shmups at all like Gigo Takadanobaba, Taito Ikebukuro, Taito Shibuya, Taito Odawara, and probably others I forgot. I mentioned earlier that arcades are on the decline in Japan — shmups are on the decline of the decline. I am learning that they are basically the videogame equivalent of a niche underground music scene in a world of massive international music conglomerates.

You better cough up those coins!

Shmups in the real world

Playing on real hardware in real arcades instead of at home presented me with some harsh realities. The most obvious one? Having to pay for each attempt. That’s basically the definition of an arcade game. Even though it’s bleedingly obvious I didn’t know what it meant until this trip. I remember dying a few times in stage one and feeling like I had just wasted money. It makes me consider if such a feeling led to the demise of arcades in the 1980s with the advent of home consoles, as if videogames at home were a godsend for saving money and that arcades were outdated. For my goals, having to pay for each credit meant that it incentivized playing cautiously since I wanted to clear Espgaluda 2 more than I wanted to score well in it. It had the inverse effect too: if I game overed late into a run, putting another credit in to get less than a stage or two’s worth of money was a waste. I wanted to make my money count. Ultimately I was okay with paying for each credit. I actually like using cash. The novelty of using a foreign currency and the tactile satisfaction of handling coins and putting them in the coin slot was appealing. I bought a coin pouch thing with the Mikado branding on it and it was my ammo bandolier for those late night grind sessions. I liked the clunk of the 100 yen coins go down the chutes and hearing the sound effect ring out from ingame; it felt a bit more real than I’m used to. But perhaps the most important reason I was okay with paying is because it felt like I was somehow sustaining a culture, staving off its death, proving that there is still interest and attention for a gaming experience in the process of being lost to time.

Even the act of using an arcade cab could be puzzling. A lot of the time the button layouts differed between machines meaning I couldn't get too comfortable when swapping between games; nothing like rebinding keys at home. The autofire button for Espgaluda 2 was in an uncomfortable spot for me and there was nothing I could do about it. I had to adapt, but my muscle memory was definitely gone. Other quirks arose from the unavoidable fact that these are machines meant for public use: the buttons on the Espgaluda 2/SDOJ cab at Taito Tachikawa weren't totally reliable. A few times I would hit the bomb button and nothing would happen. I recall fighting game legend James Chen mentioning in a stream somewhere that he would smack the buttons in the arcade out of habit for this reason; perhaps this is just a normal accepted thing of arcade gaming to which I was naive. An annoying part of not knowing the button layouts either was my confusion at how to return to the game select screen on the Exa cabs — at Taito HEY I had to ask a staff member to change games for me, and it seemed even he didn't know (he resorted to resetting the machine), but at Mikado Takadanobaba there was a clearly printed message with instructions. Disregarding the games themselves, how you even play a game in an arcade was new to me.

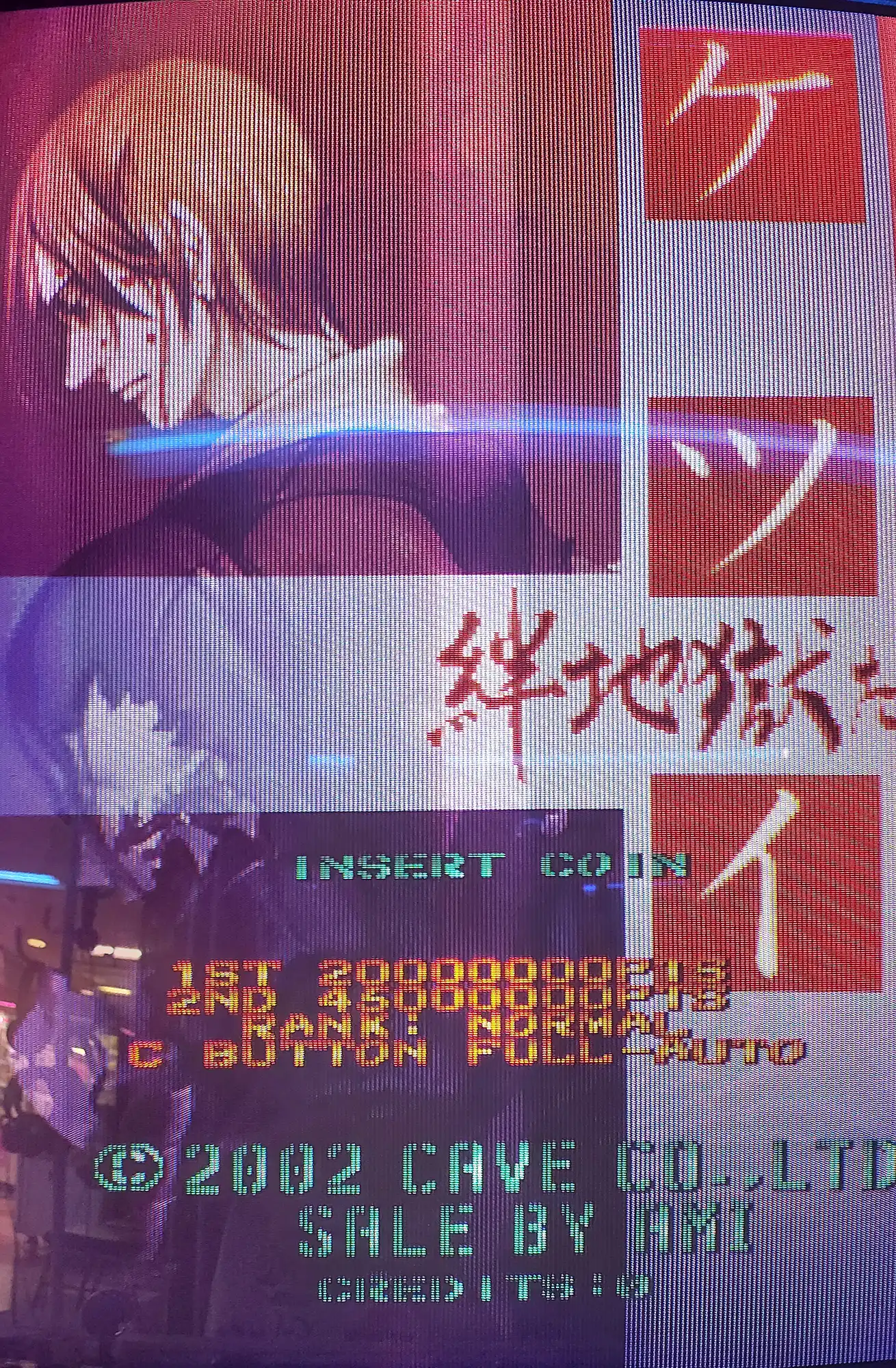

Seeing this in person is what made me buy a CRT for myself.

The first thing is the technical differences between a home port and the original arcade release. At the time I was so used to the Switch port of Espgaluda 2 that the aspects of the arcade version that differed were sorely obvious, one being the greatly reduced input lag. I can’t provide hard data or anything but I could just tell the arcade version was much more responsive. It felt like my inputs were instantaneous, like there was a direct link between my hands and Ageha’s movements, rather than a layer of emulation separating us. I’m not sure if it actually improved my skills or anything, but again, I get why arcade purists go crazy for stuff like this. This one will be obvious if you already know about the hardware quirks these games were built in mind with but the slowdown is different too. Particular parts of the game suddenly felt different with either the Switch port being faster or slower than real hardware, completely throwing me off in certain places. The scariest example is that the final boss’ final pattern is faster on real hardware than it is on Switch.

But even if somehow the home port was completely accurate, I'd only have been playing it as that. A port. At home. In my room. With an upfront fee and that's it, and not as an arcade game. I may as well have basically cheated my way to some level of competence in the arcades after playing at home; the sci-fi movie equivalent of doing VR holo-training before being dumped into a real battlefield. This is all to say that my experience of developing shmup skills at home is not commutable with doing so in an actual arcade. Without access to practice modes, save states, a familiar controller, and even the readiness of playing the game at home, all I could rely on was my previous knowledge and whatever natural skills I possess. Working my way up from zero on location is an experience I will probably never have. Not to say that one is better than the other, but during this Tokyo trip I got a taste of it; I cannot truly comprehend the concept of players achieving such extreme levels of precision and mastery all in a specific environment, in a specific location, requiring payment and beginning from the top each time. The avenues which superplayers take might be different, but their destination of godhood in the shmup pantheon is the same. Playing these games in their natural habitat made the nature of shmups clear.

Above all was the undeniable fact that these arcades are some of the few places left in the world where shmups can be played communally. Personally speaking these games are an exceedingly solo effort, and I’m not just talking about the fact I’ve been playing them without a player 2 — I’m just one guy at home. Seeing the physical presence of these games made it clear that the community exists in reality too. I would eventually come to identify HEY regulars, seeing strangers become part of the scenery. I particularly remember a serious looking guy with bad posture locked into Mushihimesama (and Futari) on Ultra mode, the SDOJ maniac with whom I traded places a lot as his game of choice and mine shared the same cabinet (this guy would pull off some insane scoring moves, accidentally mess up one thing in stage 5, and then just suicide all lives away to game over instead of seeing it through to the end), the salarywoman I saw perfectly microing through Jakou’s meanest patterns at the end of Espgaluda 1, the baseball cap dude rocking DFK, just to name a few. Even if they were strangers to me, actually seeing real people play these games in real life was… inspiring. It simultaneously made me feel like I somehow belonged, but I also lamented the fact that I recognized I was a bit starstruck (?) and that barely any of this exists in Australia. It made me feel like I was bearing witness to something special. Not only was this emblematic of the last vestiges of the golden age of arcade gaming, this was something I had never experienced before at all. While I prefer singleplayer games much more than multiplayer games, that doesn't mean I enjoy the sheer solitude. I like to play them in a communal setting. Shmups bridge this gap like nothing else has, and this Tokyo trip made it crystal clear that it was something I had been missing.

Seeing these other players in real life, with their own goals, skills, and motivations, made me want to succeed. I set a new goal: clear Espgaluda 2 on a real cab in a real arcade. With one clear already achieved at home, the minimal input lag, the gorgeous CRT look, the atmosphere and excitement of the arcade, I felt like I might actually be able to do it.

Waiwai

I knew I was on the right track.

The final arcade I visited was the Waiwai game center in Fujimidai. I’d known about this one from its weekly Twitch stream (as mentioned in On Shmuppin’ 1) but I had to see it in person. Being the furthest away from where I was staying I basically had to dedicate a whole day to visit this arcade. Sequestered away in a relatively normal-looking urban neighbourhood, Waiwai was perched on the second floor of a building and housed probably the most memorable arcade experience I had during my stay. As I entered I immediately felt the hospitality — I was greeted by Yoshii-san, the owner, who showed me around and even offered me a drink from the vending machine which I was really thankful for. After some conversation and pointing out the various games available, he left me to play a few credits of Espgaluda 2.

Some of the cabinets were customized with video adjustment dials and nearby was a large tate monitor and a rack of AV gear below, presumably for the livestreams but also with a sign that said for a small fee you could purchase a DVD of your recently recorded run. I could tell they took pride in offering the best possible arcade experience for serious players, and not just catering to children to waste their parents' money. After a couple of credits I noticed someone waiting so I let them have a turn. I expected to just hop on to some other machine, but since the game was hooked up to that large monitor, I figured I’d watch. I can’t exaggerate how glad I am that I didn’t go play something else. This person ended up being YOZ, the Espgaluda 2 world record holder. I’ve already covered what the spectator experience of Espgaluda 2 scoring is like in On Shmuppin’ 1 but it could not have prepared me for this. I could've easily picked any other day of the week to visit Waiwai but instead I just happened to go on a day when the literal world record holder was there too. Seeing him effortlessly weave through thousands of revenge bullets, earning both score extends in stage 1 (!!), making the FPS slow to a crawl almost the entire time, milking everything, it was clear that I was witnessing a master at work. He cleared with a final score around 950 million points which obviously is an incredibly good score, but considering how it approaches rivalling the world record of just a bit over a billion points, it’s insanity. Even now I’m taken aback that I was able to see such a display in the flesh instead of it being relegated to a bad quality youtube video that’s old enough to drive.

It grounded my view of what skill is in these games. YOZ was a real person, just a normal looking dude casually using his phone while waiting for me to be done before hopping on and absolutely destroying an extremely difficult game. We’ve heard it all before in interviews with famous musicians or artists who all say they’re just a regular person, they’re no one special, and that we as the audience understand where they’re coming from — they’re just a normal human being. But where this experience in Waiwai refocused my view was not so much in elucidating that this person was real, but more so that real people can be that good at something, that a real person was able to pull off a nine hundred and fifty million point run of Espgaluda 2 right in front of my eyes. That that kind of skill is possible and achievable and is the result of dedication, perseverance, and passion. That the skill ceiling is that high.

While in Waiwai I got to speak with YOZ, as well as Chantake, who Yoshii-san introduced as “the famous DOJ player”! They were really nice people and very friendly. We mostly spoke about shmup related stuff, both saying they’d been playing for at least fifteen years (completely humbling me), our opinions on certain games, as well as giving me some good tips for Espgaluda 2. They managed to demystify the second half of stage 5 for me, and it’s a strategy I still use to this day. I tried to demonstrate I was capable of this new strategy but I didn’t even make it past stage 3. It’s hard to perform well when two gods are watching over your shoulders. Maybe someday I’ll have the opportunity to prove my gamer worth…

Moments like these closed the gap, even just by a bit, of distance I sometimes feel playing these games at home in my room. That was why this visit to Waiwai was the most memorable and why I was so appreciative of the time I got to spend with the guys there. I made memories. I do not get the opportunity to hang out with other shmup fans IRL, let alone even play any of them in real arcades here. These fleeting interpersonal moments are what make playing these games special. While in Waiwai Yoshii-san offered me a canvas board for me to write my name and a message to put up on the wall amongst messages from other past visitors, some of whose names I recognized. If you ever drop by, keep an eye out for one signed by me, JZ! Waiwai is a must-visit destination for any breed of arcade gamer. It seems like a place where lots of well known players gather; I just wish my Japanese skills were a little better! Like Mikado they frequently hold events and livestream them. Maybe one day even I could participate.

With this newfound inspiration and knowledge I felt like I could actually succeed in achieving my goal of clearing Espgaluda 2 on a real cab. I spent a good majority of the last week of my trip at the arcades trying to grind out the clear. At HEY I was basically taking turns with the SDOJ maniac I mentioned earlier and the odd school student on break, and at Mikado I was trading places with some Futari freaks (though I didn’t wait around as much here); the only place I could hog the machine was at Taito Tachikawa as nobody else was around, but then the buttons were unresponsive. Time was not on my side. With the help from Chantake and YOZ (and a lot of 100 yen coins) I was able to reach the final boss almost consistently. I thought feeling nerves at home was tough but I was not prepared for how bad they got in a real arcade. Once I cracked reaching the final boss for the first time I felt like I could actually do it. It was like finally clearing one hurdle at a time. I'd reach the final boss in one run, get further in another run, get even further in another, almost defeat them in yet another, but...

I never beat it. I never managed to stick the landing. At the very end of my best run, with one life left, I got Kujaku down to something like 2% health, then during a lull in the intensity of the final attack I had a lapse of concentration... and I walked into a bullet. When this happened I accidentally yelled "NO!" and the baseball cap guy playing DFK next to me laughed. I got ridiculously close multiple times but it just wasn’t happening. During my last day I spent basically all the time I had left at Mikado trying to get the clear before having to acquiesce to my losses and say goodbye to what amounted to a random building for which I’d somehow developed a sentimental feeling.

man.

After returning home I sought to improve. Espgaluda 2 still called to me. I cleared it twice more on Switch, then purchased an Xbox 360 and CRT television, and cleared it again with my best score so far. This last clear certainly wasn’t flawless but it was the one in which I finally achieved a long time goal of mine, which was clearing with more than one life left. With a game as tough as this I felt my resolve strengthen. If I ever return to Tokyo I’m confident I could win a rematch, and maybe even do it at Waiwai. Even though there is still so, so much to do in this game, I felt the beginnings of competency, like I didn't have to scrape past the finish line each time. This is a new chapter in my shmup knowledge and experience, one that I am yet to see where it takes me.

Even now, after a more than a year of playing these games, I still find myself facing the same kinds of challenges as I did on day one. I've put Espgaluda 2 aside for now and I'm working on another main project, for real this time, and it is a Ketsui 1-ALL. To put it bluntly, I'm getting owned. I've put 25 to 30 hours or so into practice and attempts and I'm getting destroyed by this game. It feels completely different to Espgaluda 2; Ketsui is much more aggressive and fast paced, requiring you to speedkill a lot of enemies or face being relentlessly crushed. It reminds me of when I was in the midst of learning Espgaluda 2. Looking back on those times now I kind of can't believe I was finding certain parts tricky or that I didn't know how to do a certain thing. I'm not saying I'm excellent at the game or anything (the leaderboards on restartsyndrome prove otherwise), but after having put more than 130 hours into the game I feel like I know what a good 1CC looks like. I can tell when I have performed well and when I haven't. I am nowhere near this with Ketsui. Most of stage 4 and 5 are still a mystery to me, even parts of stage 2 and 3 scary, and this is without having done many actual 1-ALL attempts. There is a wide gulf between practice and doing it for real. I like to remember a good piece of advice from this youtube video I watched from an author answering viewer questions about researching and writing. He says that boredom or disliking a project happens when you haven't done enough work on it, that boredom is a plateau reached you've scratched the surface, and you need to go deeper. I've been here before, and it's where I currently am with Ketsui. The only way forward is through.

A response to my past self

In my previous post I wrote:

“Were these games ever meant to be 1CC’d, let alone grinded?”

The answer?

Yes.

They are meant to be 1 credit cleared. They are meant to be mastered, they are meant to be scored, and they engender the utmost skill. Of course some arcade games were designed to eat your money, but when you find one that feels fair (instead of a rigged carnival game) it offers a gaming experience unlike anything else. In my previous post, when I doubted the fact that games as hard as these were somehow meant to be cleared in arcade establishments, all I knew about the word "arcade" is that they are places for claw machines and prize games. I could not have fathomed the idea of people going to the arcade to train, to exercise skill, to compete. That’s what it was all about. If you died 10 seconds into the first stage, too bad. You gotta learn. This is absolutely nothing new to people who are already into arcade games, of course, but to me, it was. No other gaming experience has satisfied this craving. No other gaming experience has gotten my blood pumping like this. I have never wanted to ravenously know a game inside and out as much as this before.

I’m gonna keep playing.