On Shmuppin'

Background

I’ve been wanting to write on my experience with shmups for a while. I’m relatively new to the genre, only having really played them for around seven months, yet it completely has me in its claws. And I don’t think I want it to let go. I’ve had so many thoughts and encountered so many new things since embarking on this journey and I don’t really see too many people out there sharing their experiences from the perspective of a “sort of noob”. I’m writing this after having just cleared Espgaluda 2’s arcade mode which has been my longest shmup undertaking so far. I won’t be focusing on shmup design or the history of the genre or anything like that; these are just my experiences and thoughts. So far of the games I’ve cleared, they:

- Are games developed by CAVE

- Are bullet hell games (remember, bullet hell is a subgenre!)

- Were played for survival/1CCs, and not for scoring

- Were played at home, emulated, or via ports, and not in real arcades on real machines.

I say this to offer some perspective of where I’m coming from. This is a limited scope of what the genre has to offer and I’ve barely scratched the surface.

I believe my first ever exposure to the genre was a classic 144p video titled THE HARDEST VIDEO GAME BOSS EVER! that I’m sure every shmup player knows about. It’s a video from 2007 of someone credit feeding through Mushihimesama Futari’s last boss on Ultra difficulty. The seed was planted. I even found some of my own comments on that video from 2009 — “if this was a coin op game, they probably made it so hard that the player would hae to spend atleast $10 to beat it.” Insightful. After forgetting about this video I tried Touhou 7 perhaps in the early 2010s, Ketsui and Mushihimesama Futari via MAME somewhere in 2014-2015, then dabbled a bit in Mushihimesama and Dodonpachi Resurrection’s PC ports in 2016 and 2017 respectively. At some point I tried Radiant Silvergun, thinking it was one of the coolest games ever, as well as some other shmups on steam like Ikaruga, Jamestown, Crimzon Clover, and Danmaku Unlimited 2. I didn’t get very far in any of these. They may as well have amounted to 10 minutes of amusement before I quietly closed the game and moved on with my life. For a while Dodonpachi Resurrection remained my worst value “dollars per time spent playing” game on steam, as a $30 USD game I had around forty minutes in. The idea of actually spending time with these games did not cross my mind.

It wasn’t until the announcement of the Nintendo Switch port of Radiant Silvergun in September 2022 that I started playing these games for real. I had an epiphany — “Hey, I actually like these games.” And so it was. I decided I wanted to 1CC Mushihimesama on Novice Original because it seemed like an attainable goal and I already owned the game. I bought a cheap arcade stick, booted up the game, and off I went. I was determined to not repeat my past ten minute fling with it but as a brand new noob I didn’t really understand why my strategies worked or not; I began to sort of understand what the game was asking of me, such as the importance of positioning, timing, precision, etc., but at a shallow level. It didn't help that with the absence of a real practice mode for novice difficulty attempting the clear felt like trying to thread several needles in a row. Somehow I eventually managed to pull it off, which ended up taking somewhere between 15 and 18 hours. At any rate, it was a clear, and as my first ever I'm proud of it. The novice mode is nothing to sneeze at especially when you consider the Super Easy modes M2 includes in their recent ports.

The next game I wanted to tackle was Ketsui. Shmup fans might laugh at this decision. I remember it as “the game with the boxes with numbers on them” but nothing more. My interest in the game was piqued as I had learned that an EP I really liked, Commissions II by Oneohtrix Point Never, very prominently samples some tracks from the game. Ketsui went from nothing to being a number one priority, in a bold red font, with "URGENT!!!" next to it. So I did, and I promptly got my ass kicked. Ketsui is known as one of CAVE’s hardest clears yet I still soldiered on, at least for a bit. Emulating the game in MAME meant for easy use of savestates which is how I practiced, but after a while I realised I was getting nowhere fast. The game is significantly harder than Mushihimesama’s novice modes and I felt like continuing was futile. K_sh in my twitch chat recommended Espgaluda as it’s a much more manageable game, some even calling it the CAVE gateway drug, and that was the real inception of my shmup odyssey. Ketsui still lingered in my mind but there was no way I was going to make any real progress with the skill level I had then.

Espgaluda became my obsession. The music rocks, the characters and stage designs are cool, and the story was intriguing. I didn't want to play other games. With the small amount of knowledge I had gained from Ketsui I made savestates and repeatedly practiced them until I felt like I was ready to move onto the next section. I covered the whole game before trying to clear it for real, and would return to practice if I felt like something needed work. Attaining the clear felt feasible which was a big help in assisting my motivation to continue playing it, yet, of course, I had my humbling moments. An early PB was pretty much the result of a fluke and I didn’t surpass it until much, much later. Sometimes I would luckily scrape by and be unable to repeat it. Even though the game was easier than Ketsui it was still very difficult at times, and sometimes maddeningly frustrating. As my first arcade clear project I encountered new issues not present during my time with Mushihimesama’s Novice Original: sometimes I couldn’t even exit stage 3, sometimes parts I thought I’d mastered in practice would end runs, sometimes nerves took hold and I would choke. I persisted, returning to practice to iron out any kinks. I knew I was getting closer and closer. After around sixty hours of practice and attempts, on 30/12/2022 I finally cleared it. As the result of a lot of blood, sweat, and tears put into practice, for my first arcade clear, it is dear to me. I sat there in the afterglow and felt power coalesce within me. Even if I look back at the video and think “I really found this pattern/section/game hard?” I knew I put that effort into it and it paid off. Shooting games satisfied a craving not much else came close to: I had long desired a gaming experience that required time, commitment, energy, skill, and then seeing the results.

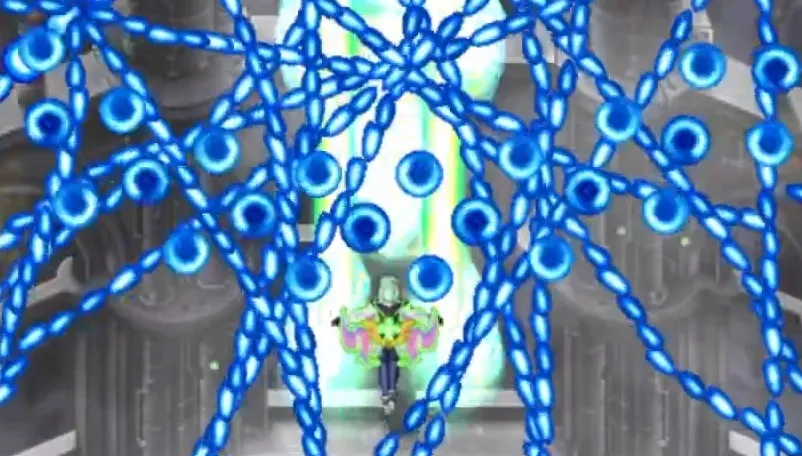

Sometimes it's just you against the world... or maybe thousands of bullets.

The next logical step is Espgaluda 2, right? I purchased the Switch port and, much like Ketsui, got my ass handed to me. This game is a huge step up in difficulty over its predecessor and I quickly shelved it in favour of ESP Ra.De. as that seemed like a more reasonable challenge; one that would still push me but not as much as Ketsui. I played the PS4 port and approached it essentially in the same way as Espgaluda 1 except it was facilitated much more easily by its excellent training mode. But… it didn’t click like Espgaluda 1 did. Espgaluda 2 was still in my mind, even if ESP Ra.De. seemed like the more “sensible” choice. At the advice of a friend I returned to it. Espgaluda 2 ticked more of my boxes and that was enough to continue playing it, regardless of the difficulty. I was enticed by its dreamlike atmosphere, trance music soundtrack, the gorgeous backgrounds, the familiar faces returning from its predecessor, and the knowledge that if I could pull this off, it would be an undeniable accomplishment. Expectedly, this game really pushed me to my limits. I employed a new practice method (which I will discuss later) which emphasises tracking and pacing your experience of the game and provides a more solid basis for practice. I had a long road ahead of me and I felt like this would be a good time to try something new. Espgaluda 2 is unrelenting in its difficulty and requires the utmost precision to get by. I encountered deeper versions of problems faced in Espgaluda 1: progress seemed slower (but still steady), nerves set in further, and the increased difficulty meant that there was less room for mistakes. One slip-up could prove disastrous. For every problem solved it seemed another two sprouted up elsewhere. The experience of getting destroyed in real runs during parts I thought I'd mastered in training mode was really a symptom of a larger fundamental issue: I had to wholly improve my shmup game. I did see progress as the amount of times I was able to no-miss sections increased but only around the time of the 1CC did I start to feel like I was beginning to truly “get” it; a lot still felt like I didn't understand what was going on or that I was relying on luck too much. After around 90-95 hours of practice and attempts I finally got the clear on 02/04/2023. It’s too soon to say what I really feel about having accomplished this but so far I’m just happy the practice paid off.

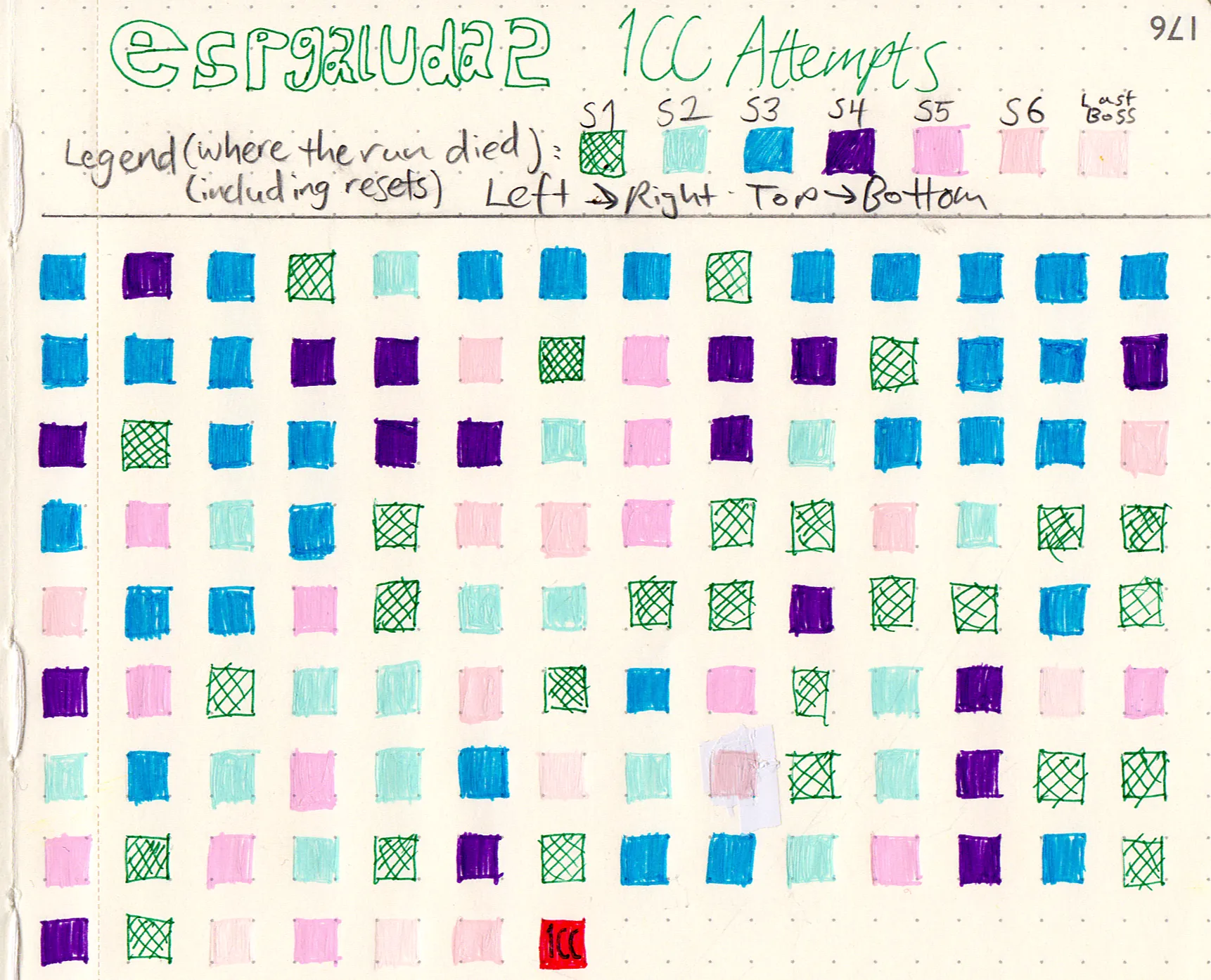

For every 1CC attempt I drew a square whose colour corresponded with where the run ended. I don't know why the colours are bad on the scan, but you get the idea.

I also wrote down the time and date of every 1CC attempt as well as filling out a grid with colours corresponding to how far I got in that run. Some stats:

- First time reaching stage 3: 1st attempt

- First time reaching stage 4: 2nd attempt

- First time reaching stage 5: 20th attempt

- First time reaching stage 6: 20th attempt

- First time reaching stage 6 boss: 39th attempt

- First time reaching the final boss: 83rd attempt

- Actually beating the final boss and therefore getting the clear: 117th attempt

The Mental Game

Shooting games are a new endeavour for me and they have presented me with a lot of food for thought. My only real previous experience with skill gaming was speedrunning, but I never went as far in it, mentally and physically, as I have with shmups. Playing for skill taps into a deeper aspect of gaming, one closer to mastery rather than entertainment. It’s the difference between being the athlete and merely watching them. So much is required of the player for success, and that’s why I keep coming back. And as I keep coming back, I encounter new challenges, more things to reflect on, my limits tested, my purpose thrown into question.

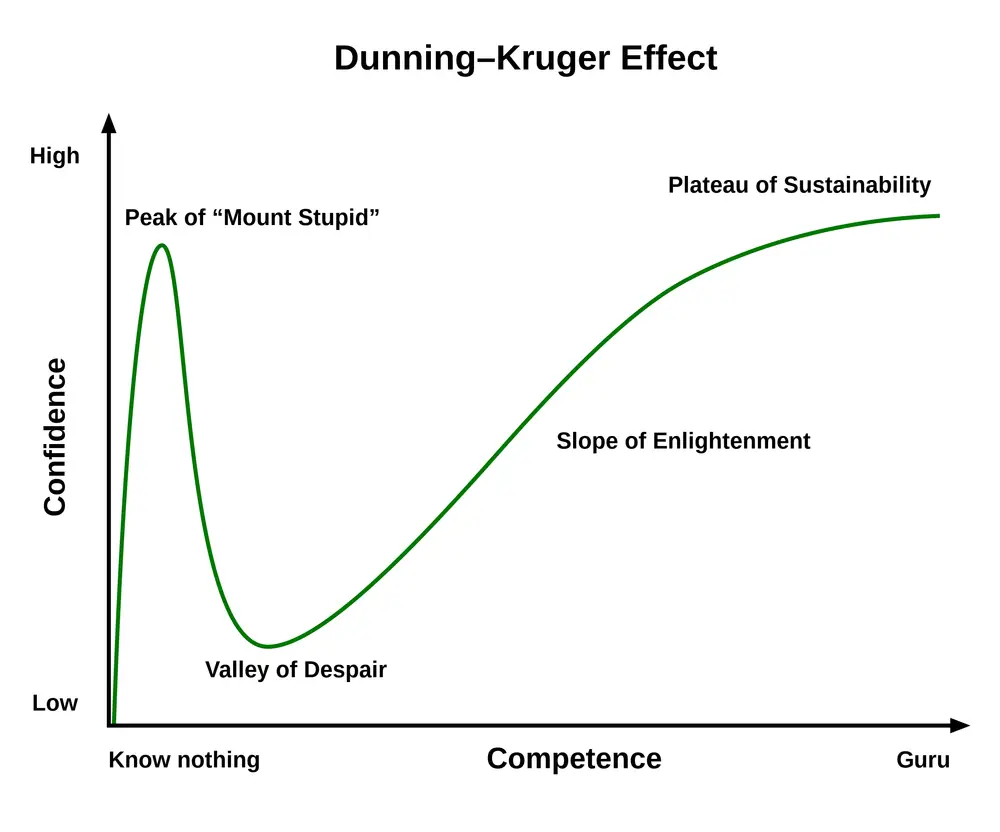

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a psychological bias wherein newcomers to a certain field or discipline with low ability tend to overestimate their abilities. While there are multiple interpretations as to why this happens, I believe it has to do with the outward perception of what counts as important, relevant, useful, or even impressive aspects of the field in question; with shmups, specifically bullet hell games, the perception is that dodging bullets is key. While unavoidably true there is a lot more going on. Consider why the aforementioned HARDEST VIDEOGAME BOSS EVER! video and its kin even exist, why they’re popular, and why the comments on those videos are popular. The spectacle of a thousand bullets onscreen and a lone ship/helicopter/guy with wings/teenager riding a bug somehow having to weave through it is tantalizing, but I feel like few actually look past this. The adversity on display is astounding, and so newcomers to the genre, whether they actually play the games or not, see the bullets and the micrododging and not the dozens of hours of practice and planning that went into that perfectly executed 1CC video. They don’t see the joy of precision, of dedication, of mastery, the satisfaction of blowing shit up. I don’t remember if I ever solely thought “all I gotta do is dodge good” but I remember being influenced by this thinking. There were moments were I believed progress was only inhibited by my poor dodging skills instead of the truth. My tipping point was when I was trying to learn how to fight Jamadhar in Ketsui: There was one pattern I just couldn’t make work, and my judgement was clouded because I felt like I just needed to dodge better.

I was getting my ass handed to me on a silver platter by Ketsui. B-but… what if I can’t…dodge good?! I was humbled. I went from thinking I was on top of the world to being back at square one. I had to take a step back and realise that the only way I would ever triumph over Jamadhar was to get better at the genre as a whole. Yes, by beating my head against a brick wall I would probably break through it at some point. But wouldn’t it be better to, I dunno, learn to find a sledgehammer or something first? This cycle I think is the core of the Dunning-Kruger effect, and is vital to be aware of when pursuing any skill-based activity. You begin, you make a bit of progress, you think you’re getting good, you get owned, you think you’re trash, you make a bit of progress… This really does go on and on, even now. I know I’m better at the genre than I was before, but I still have a way to go. People who are at the top also have a way to go. I think just being aware of this cycle and putting a name to the face of Dunning-Kruger assists in keeping your expectations in check and not spiralling down into a miasma of self-deprecation.

A visual representation of the Dunning-Kruger effect. The process of mastery is repeatedly traversing this slope but gradually trending upwards on both axes.

A real example of this is as follows: There’s a great channel on twitch which features live gameplay direct from the Fujimidai WAIWAI game center in Tokyo, and it has featured high level scoring gameplay of Espgaluda 2. I don’t know who the player is but their skills are incredible. Their movement is on the level of a TAS, their positioning is perfect, their planning and route is absolutely insane for how much it differs from mine (since they’re scoring and I was just playing for survival). Bosses are left alive uncomfortably long to let the densest patterns come out, waves of bullets are effortlessly herded into a cluster, enemies singled out to cancel all bullets onscreen instead of just speedkilling everything, the game chugs to 5 FPS, the score counter soars into the hundreds of millions. I watch this stream with my eyes glued to the screen and I literally recoil in horror when they die to some random popcorn. It’s totally engrossing. And as I was watching, all I could think was how the skill ceiling is astronomically high in these games. This person was finishing the run in stage 6 with 700 million points, an incredibly strong score, obviously annoyed as they mash through the Continue? countdown timer after losing their last life right before the end. And there I was, sweating bullets after (merely) having no-missed the stage 2 boss. We were on completely different planes of competence. It was a different kind of humbling because I didn’t feel like my skills were called into question or anything, it was more like a sudden slap in the face of just how far these games can be pushed. I think I’m currently in a good place in my life where something like this isn’t too affecting, but someone a little less emotionally stable might take this badly and feel like their progress has been for naught. I feel like I might’ve had that experience during my speedrunning stint, but not so much during my time with shmups for a variety of reasons. In instances like these I do like to remember the Holy Shit Two Cakes meme and its further variations.

So far what I’ve discussed mostly manifests in the context surrounding the games instead of within them. It’s the culture around the games, the scene, human nature. What I have not touched on yet is what happens in the middle of a shmup sesh where you feel like this might finally be the run, and your fingers start to shake, your heartrate increases, you sweat, and you hunch over way too much. I’m talking about nerves, and they’re real. While this does tie in to the “recurrent humbling” I mentioned earlier this is a little different as for me it was ongoing. Every run of Espgaluda 2 felt scary. Certainly the tensions rise over the course of a run in any game but in Espgaluda 2 I rarely had a moment of peace while playing. I never reached a point where I could “comfortably” complete any section of the run. I streamed both my Espgaluda 1 and 2 1CC attempts while wearing a heartrate monitor and I was easily reaching 140-150 BPM when things started to get scary, and even higher when the 1CC was close. I literally started shaking when I was in the final pattern of the final boss of Espgaluda 2. Even though my skill level increased with more experience and exposure to the game, I expected to be calmer and only feel nervous once a run had a chance at becoming The One. This was not the case. In Espgaluda 2 sometimes I would feel nervous at something as low-stakes as the stage 2 boss going well. I can’t tell if this is because of my lack of experience with the genre, with a particular game, with skill gaming in general, or my disposition.

What I did find, however, were some ways to combat this. Mark_MSX of The Electric Underground youtube channel talked about repeating a mantra in your mind; if I remember correctly, his, when completely out of resources, was something along the lines of “I’m just gonna have to show them how good I am at dodging.” Mine was perhaps a bit less valiant-sounding: If I had no-missed stages 1 through 3 in Espgaluda 2 I would think “c’mon John, that’s half the game! You have stage 4/5/6 left!”, or even “shut up brain!”, because it really is just your brain doing stupid shit at the end of the day. I do remember using “no fear” as a mantra when push came to shove during Espgaluda 2, and "you got this" during the scary bits of Espgaluda 1, and they worked. Another way to improve on this is more experience with the game. I can say some maxim like “experience breeds confidence” and it’s not even wrong. The more I practiced a stage and then had real experience with that stage in a real run the nerves would settle a bit, but they would never disappear. Any good run will probably feel scary at some point, and the buildup of tension is no joke either. There’s a reason why my Espgaluda 1 and 2 clears end with me yelling and screaming. Practice paying off with a huge victory is unbridled elation. Precision, mastery, dedication, luck, skill, chance… a melting pot of human imperfection facing machine adversity…

Method to the Madness

The only way I was going to stand a chance at clearing these games was to practice. Practice, practice, practice. God only knows why the devs of the Mushihimesama port didn't allow you to select novice difficulty in training mode so I literally had to start from the start every time, and there was no way I was going to repeat that agony. Luckily I live in current year where there are a lot of resources available. I’m not going to parrot the teachings of ProMeTheus in The Full Extent of the Jam (which I read early on and am unsure how necessary it is but it’s nice to have anyway), but suffice to say, practice makes perfect. For each of my two arcade clears I used different practice methods and I'll discuss how both went.

I emulated Espgaluda 1 In MAME and made a lot of savestates. I made savestates at the start of a stage, at its midboss, its end boss, and at any other tough segment. I repeated each section until I felt like I had some grasp on it before moving on, and then I would try doing whole stages at a time to make sure it stuck. This allowed me to at least block out practice but it was far from a perfect method. One flaw was there was no concrete way of deciding I was “done” with a section other than, well, assuming I was now competent. Another is that I played each section basically in a vacuum, which I’ll touch on more later. The worst aspect of this was, if I made a savestate after the game did an RNG call, whatever that RNG call determined would happen in the exact same way every time. That’s the opposite of RNG. For example, for a bullet pattern that rotates, the angle it spawns at would be the same every time, and so I would learn how to deal with it in a specific way. I was learning and committing to memory a very specific iteration of the game which did not prepare me for real runs at all. I would come to expect enemies to spawn in exact places or things to happen in a certain order, and then in real runs when it was different, it was disorienting and frustrating. It limited the scope of knowledge I could acquire via savestate practice and only served to emphasise its flaws. While it did have the benefit of giving me the general gist of how things would play out, it necessitated doing real runs to get the full picture.

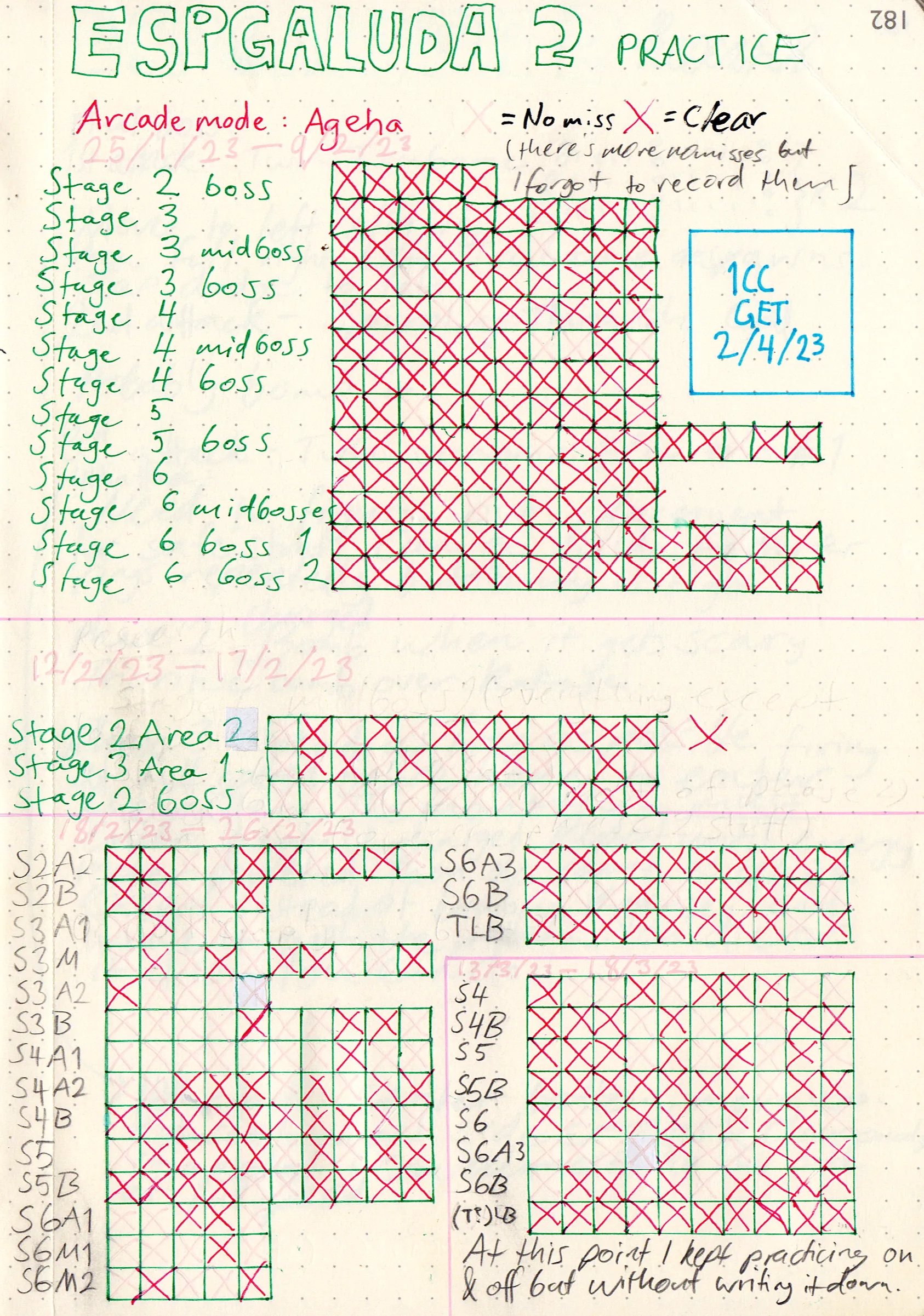

The training grid I used. A red X for a clear and a gold X (just trust me, my scanner can't capture how magnificent of a fluoro colour it is) for a no-miss clear.

For Espgaluda 2 I played the Switch port which has a decently furnished training mode yet it is far from robust. You can start from a few predefined checkpoints, namely the start, midboss, and boss of each stage, change some game parameters, resources, character, etc, but nothing like the granularity of savestates. Of course it is better than nothing, and again, the fact that I cleared the game using this training mode must mean it somehow works. There was also the benefit of the RNG call limitation basically being nonexistent. This time I employed a training regimen adopted from Sterny’s Painless Progress Method which I found out about from his blog and his interview on Shmuptopia. I did this because I wanted some concrete method of ensuring I got enough practice in. It was not enough to only “feel like” I had enough; I wanted it in writing. I wanted an obvious goal and discrete data. So I drew ten or so boxes for each stage, midboss, and boss, and drew an X in the box when I had cleared that bit in training mode regardless of how many resources I used, yet still trying to bomb as little as possible. I didn’t play a segment more than twice in a row and I worked down the list, so as to cover the whole game rather than grinding one thing repeatedly. At some point I started using a different colour X if I had no-missed that section, which was mostly for my own amusement since it might put some unnecessary pressure on me to perform well, but it was definitely nice to look back on. You can see a visual representation of progress in the form of the proportion of no-miss clears subtly increasing over time. Once I had filled out the grid I would do some 1CC attempts. Then, if I didn’t get it, back to training I went. I did this cycle a few times, adding more boxes as necessary and tailoring them to what I felt needed (or didn't need) work. In terms of getting and ensuring raw experience this method was excellent. It made practicing Espgaluda 2 more like training rather grinding. It was motivating to break down the lofty, almost formless goal of “1CC” into much more manageable bite-sized pieces. Instead of “do it til it feels right,” it became “for now, complete this column/row of the grid.” It even put a cap on play sessions too, which is especially important for retaining information as well as preventing burnout. I didn’t fully adhere to Sterny’s method (I didn’t alternate weeks with another game and sometimes I went over the 60 minute suggested time limit), but so far so good, right? Where this method failed was when I really needed to dig deep into a certain section. I understand I could’ve made more and more specific training grids, or even added more boxes per section. I understand I could’ve made an entire page of boxes dedicated to a specific ten-second long area in stage 6. But at some point it felt futile to do so, and, like Espgaluda 1, what I needed was more experience in real runs.

A limitation of both of these methods is that it was easy to get tunnel vision in one way or another. In the case of Espgaluda 1 because I had access to the fine granularity of savestates anywhere in the game there was nothing stopping me from grinding a tiny microsection of the run repeatedly, like a broken record. Not only does this accelerate burnout, but, much like the issue of repeatedly facing a stale RNG state, it also prepares you for one specific version of the run; your resources are the same, your lives are the same, you start to expect to arrive there in a real run in that exact configuration of the game scenario, when in reality anything else is much more likely. It was like I knew how the song goes but I didn't know how to perform it. In Espgaluda 2 tunnel vision was still possible but what happened instead is I felt overconfident in my practice runs because there were no consequences for failure. Training mode was like a safety net, a neutral space to try stuff out. Which… is what you want, right? That just makes sense. A safe place to test out strategies and ideas. A laboratory. I know it sounds obvious but it really did feel like whatever progress I was making in training mode almost didn’t matter if I couldn’t pull it off in a real run. I was easily frustrated by this. This is why I mentioned earlier that I never felt comfortable in real runs. With the benefit of hindsight I now understand that I was making progress but I just couldn’t see it because of that tunnel vision; the safety of training mode made me overconfident and the extreme humbling of real runs kinda hurt sometimes. Perhaps my expectations were askew. That’s what I missed while staying in Espgaluda 2’s training mode. Real runs require more of the player: improvisational skill, memorisation, raw game knowledge, tactical usage of resources. Perhaps the point was to never master each section in isolation and then just chain them all together in a real run. I needed more real experience. This is a place I have some issues with the training method I employed for Espgaluda 2. Its purpose is to block out and stagger the acquisition of raw experience. What you actually do in those segments is a different question.

The long and short of routing a survival clear is the balancing act of managing resources, incoming enemy bullets, and speedkilling and prioritising targets. Okay. I could do that. I could play a segment repeatedly and make a mental note of where enemies spawn and stuff. I could even watch my own replays to add a bit of distance between myself and the game so I could study it as an observer. Fine. I got through Espgaluda 1 this way, and I even did a bit of research for Espgaluda 2. But what happens when it doesn’t work? For the life of me I could not figure out stage 5 in Espgaluda 2, I just couldn’t. It still eludes me. And so there is another ace up your sleeve…

I eventually learned that watching replays of others is a condoned and even suggested manner of gaining insight for how to clear a shmup. There might be some walled-garden secrecy amongst some players out there but I really don’t know enough about the scene as a whole to say anything (and I definitely don’t want to make sweeping generalisations that I can’t back up); most of the time it seems like sharing strategies is encouraged. Some stuff just seems nigh impossible until you watch a video on youtube and then it clicks in your mind, and you wonder how you ever found it difficult at all. That’s cool and all, and I definitely do that now, but I want to talk about how I arrived there. When I was knee deep in Espgaluda 1 I had some conflicting thoughts regarding watching other people’s runs in order to gain insight. I remember not wanting to see anyone else’s runs because I felt like I could do it all myself. A few people in my twitch chat gave me tips for certain parts of the game or guidance for better gameplay strategies overall, which was the extent of the outside assistance I received; I was okay with this but I still didn’t want to watch anyone else’s runs. The reason, if I am even remembering this correctly, is too long to explain succinctly but I’ll break it down.

I'm familiar with the layout of the Spencer Mansion like the back of my hand. Even though it's a horror game, somehow it's comforting.

I used to be very into speedrunning Resident Evil HD Remaster. I learned the category where you get the best ending as Jill Valentine. I knew the route back to front. I knew every room, what lines to take in and between those rooms, I would even visualise the path through the Spencer Mansion as I laid in bed as a way to calm my mind. I quite enjoyed speedrunning this game, but I did not devise a single part of the route. I copied the (then) world record run and committed it to memory. I didn’t know why they picked up a certain item at that point, why to take this strange line (other than it worked...the best?!), how much damage you could take here or there, and so on. I didn’t understand the game; all I knew was how to copy that world record video, and so my runs of the game were essentially poor facsimiles of it. I never got into the science of the game. I labbed nothing, I didn’t try any new strategies. At some point I learned that the route I had memorized was rendered obsolete by a change in strategy by the high level runners. They had moved on to using a different weapon for a certain section in the game, and I kept on using the old one, the one I remembered, because I wanted at least some aspect of this run to be mine. I needed something to make my route different than the rest of them, even if it was slower. Instead of for competition running the game became my fun little side thing. I just wanted to play this game quickly. There’s nothing wrong with this as I genuinely found going fast to be fun, and something must’ve been good about it because I did the same with a few other games in the Resident Evil and Silent Hill series as well. Speedrunning these games was pretty much just for fun but I knew I was dissatisfied with never having contributed to the art of playing that game fast. When I started playing shmups I knew I had to make a change.

In Espgaluda 1 I wanted the whole route to be mine. I didn’t want to feel like I was poorly imitating someone else’s run, I didn’t want to play it only for fun, I wanted the entire effort to be mine. To that effect I think I succeeded, barring the few strategies I learned from twitch chat. Maybe it was hubris, maybe I had something to prove, maybe I had an insecurity that I overcompensated for, but maybe I just wanted to seize an opportunity for triumph. The clear did feel like I triumphed over adversity, and it felt great to know that 90% of the route was mine. But the thing is, now that I’ve cleared Espgaluda 2 without the same craving for uncontaminated achievement as I had for Espgaluda 1, I don’t feel like my Espgaluda 1 clear was more “real” or “true” in any way. The parameters surrounding pride, accomplishment, achievement, and so on, are more nuanced than I had originally experienced. My Espgaluda 2 route is a chimera of different people’s strategies and some of my own design. Some bits I 100% did myself, other bits are 100% theirs. The parts I did myself were because I could understand was required. I could understand an ideal way to deal with it, or at least something that worked and was repeatable. The parts I copied off others I didn't understand at all. They mystified me, and so I needed a bit of help to see the way through. And finally, for parts that even copying someone else's strategies didn't help with, I would just bomb through it. That's what bombs are for. It’s probably possible for me to annotate my clear with citations of whose ideas I borrowed and when. Once I saw how others did those parts it was like the final piece of a puzzle falling into place. Not only would it help solve an immediate problem but also provide insight as to why that solution worked; the knowledge gained was more valuable than I originally thought. I can recognize a threat and categorize it. I add a new tool to my repertoire. And even so, even if I didn’t learn anything, even if all I did was copy a technique just to get this hard part out of the way, there is a more pragmatic perspective to remember: I’m the one who got the clear. I’m the one put the practice in, I’m the one who is now familiar with the game back to front, I’m the one who micrododged perfectly through Kujaku’s final pattern and then exploded with joy once I saw the bright flash of white and hundreds of 100x multipliers dance across the screen. I toed the line between speedrun fun and shmup science with these two clears, and I’m proud of both for different reasons.

An example of something I routed myself: A simple maneuver misdirects all incoming fire in the section immediately after the second midboss in Espgaluda 2's sixth stage. This one move was instrumental in ensuring consistent survivability.

The Future

I came into shmups from basically nothing. I had no childhood nostalgia, I didn’t grow up with a Megadrive nor did I visit arcades with shmups. Nothing. And so my foray into the genre was one I had entirely as an adult. This has allowed me to form a fondness for the genre based upon its own merits. I’m a big nerd for art and music and a lot of my positive response to games arises from the visual/aural aesthetic experience, a lot of the time even overriding the gameplay experience, but shmups tick all those boxes. The mixture of deep gameplay over a short burst of time, the demands of precision and dedication, the incredible music, the cool art, all of it comes together into a perfectly designed package of which I can’t get enough. I think I have a newfound appreciation for arcade games after basically having never paid them much mind before September 2022. The last time this happened was when I finally got into turn-based RPGs in my early twenties with no prior experience (not even Pokemon), but that was more me getting into a few select games rather than a genre. I don’t think I could confidently say I like RPGs as a whole, and perhaps the same is true for shmups. Maybe I really do only like bullet hell games, or games by CAVE. I have to play more to find out. But there is obviously a reason I’m even writing this.

I came across the idea of shmups as a lifestyle genre early on which was an alien concept to me. It was discussed in reference to how the culture and scene around fighting games manifests, in that they wouldn’t just play the game at home until they were done, it would become part of their life, their identity. They might go to tournaments, watch events, keep up to date with information, socialise with others in the scene, and not only play a fighting game once or twice. They don't have to play fighting games every day, or do stuff in the scene every day: It’s a stable, steady relationship instead of a fling. I don’t think I’ve played shmups long enough to know how and if they will ever settle into a similar position for myself. I would like that to happen, sure, but two (and a half) clears is not really enough of a sample size to extrapolate. Some people in the community have been playing these games for decades. Some of them, at least from my perspective as an outsider, seem to really make it part of their lives. They customize their game rooms, refurbishing arcade cabinets, playing on real PCBs, and so on. It's kind of crazy how deep it goes when all I have done so far may as well be splashing around in a puddle. It makes me wonder if there even is a future version of me out there somewhere who’s done the same as those veteran oldheads, or if this will just be a short stint like speedrunning again. I don’t think it will be a one-off thing, and I don't want it to be, but only time will tell.

When I cleared Espgaluda 2 I felt like I was only beginning to understand the game. I felt like I had just managed to scrape by and get the 1CC and that there was still so much left to learn. Hell, I only ever played Arcade mode with Ageha. There’s two other playable characters and like three other modes to dig into. I know it’s entirely within my control to return to the game but I sort of lament leaving the game in the dust like that. I’ve done this with both Espgaluda games now; I haven’t played either since I got their respective clears. And so I wondered about what my longevity with the game, or genre, even is. Why 1CC? I sure as hell didn’t come up with the concept myself. Do I see it as a nice, neat way of knowing when to be “done” with a game? There’s no saving and loading progress in an arcade game; you either beat it or don’t. Maybe collecting 1CCs eschews the purpose of these games and instead shoehorns them into an era where we want to itemize game backlogs, clears, make a nice list, make the number go bigger, share on social media how much content I have slurped up. This is coming from an avid user of last.fm and rateyourmusic, by the way. Were these games ever meant to be 1CC’d, let alone grinded? Isn’t it a little bit insane that a game as hard as Espgaluda 2 is an arcade game? Imagine going to the arcade, never having played it before, and being expected within some realistic amount of time (or money) to clear it. Maybe this is actually just normal and it’s crazy to me because I never really played arcade games in a real arcade in my life outside of claw machines and playing stuff for tickets. And being a Dance Dance Revolution fiend as a child. Maybe 1CCs don’t eschew the purpose of playing shooting games. Maybe collecting 1CCs is simply a fun gaming hobby, like getting a new patch on your jacket. Maybe making the number go bigger is fine. You could always score higher, anyway. I’m not too concerned about this but sometimes I really do wonder if I should stop playing these games as soon as I get the 1CC. Perhaps the more healthy approach is just to return to the games later in time when I want to revisit those worlds and characters. And maybe then is a good time to play for score.

Juicy.

The aspects of shmups where I feel myself lacking are probably remedied with more time spent with the genre. I literally cannot know right now how I will be approaching the genre five years in the future. I don’t know if I will settle into a very comfy groove of, I don’t know, playing some singleplayer game as my main thing and chipping away at a shmup as a side thing. Maybe I’ll still be deep in the shmup hole and be fine with that. Maybe I’ll continue to enjoy the games for what they are. Maybe I will dedicate all my gaming energy to one clear at a time and love it. Right now I think I want to take a break before tackling a new main shmup project, which will probably be a Ketsui 1-ALL. I still have a bone to pick with that game after it destroyed me, and now that I have a PS4 I can play its excellent Deathtiny port. I would like to write on that when the time comes, since I want to compare its very robust training mode and savestate feature with how my practice in Espgaluda 1 and 2 went.

These past seven months have provided me with a deeper gaming experience than I have ever had before. I had never gone harder in any single game until I played Espgaluda 1 and 2. My gaming limits have never been pushed this hard to the point where what was required of me went further than just the games. I had to balance knowledge, memorization, dexterity, decisionmaking, and managing nerves all the while avoiding thousands of blue bullets and listening to pounding trance music. That shit is so cool to me. I don’t know how to put it any other way. I don’t think I want to stop playing these games even if they pummel me into the ground. I get owned, I stand right back up. I get a little further. I vacuum up a thousand green gems and explode every enemy in a 10 mile radius. I squeeze my hitbox through the tiniest gap you’ve ever seen. Understanding eclipses confusion.